Alexandria, Mt. Vernon, and Accotink Turnpike (Historical Marker)

GPS Coordinates: 38.7112263, -77.1438454

Closest Address: 202 Belvoir Road, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060

Here follows the inscription written on this roadside historical marker:

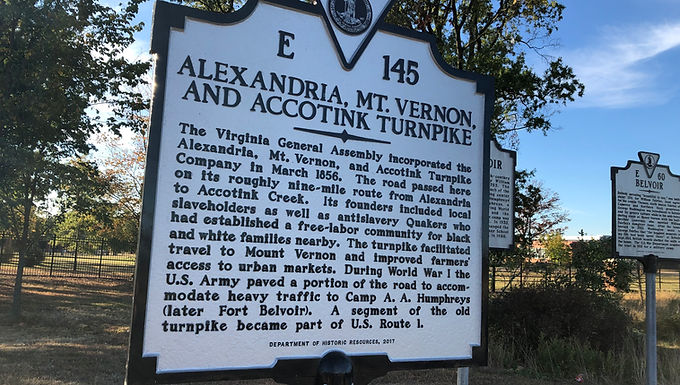

Alexandria, Mt. Vernon, and Accotink Turnpike:

The Virginia General Assembly incorporated the Alexandria, Mt. Vernon, and Accotink Turnpike Company in March 1856. The road passed here on its roughly nine-mile route from Alexandria to Accotink Creek. Its founders included local slaveholders as well as antislavery Quakers who had established a free-labor community for black and white families nearby. The turnpike facilitated travel to Mount Vernon and improved farmers' access to urban markets. During World War I the U.S. Army paved a portion of the road to accommodate heavy traffic to Camp A. A. Humphreys (later Fort Belvoir). A segment of the old turnpike became part of U.S. Route 1.

Marker Erected 2017 by Department of Historic Resources. (Marker Number E-145.)

<•>•<•>•<•>•<•>•<•>•<•>•<•>•<•>

<•>•<•>•<•>•<•>•<•>•<•>•<•>•<•>

History of U.S. 1: The Potomac Path

This is article #2 of a series that originally appeared in the Mt. Vernon Gazette.

The Origins of Route One.

Michael K. Bohn

Mount Vernon Gazette, April 2005

In early 1772, George Washington traveled to Williamsburg to attend a session of the Virginia General Assembly. At the beginning of the trip, he made the following entries in his diary:

January 25. Set of for Williamsburg but not being able to cross Accatink (which was much Swelled by the late Rains) I was obliged to return home again.

January 26. Sett off again and reached Colchester by nine Oclock where I was detained all day by high winds & low tide.

The route that he followed from Mount Vernon on the first leg of his journey south was the Potomac Path. During Washington’s time, it was a wagon road, but sections of it followed an old trail that Indians had used for hundreds of years. Almost all of the Potomac Path between Alexandria and Woodbridge still exists, but today we call most of it Route One. The current road smoothes out many of the Potomac Path’s twists and turns, but there’s still plenty of history left to see.

The Colony Grows:

Early Virginia colonists didn’t need many roads in the years following the founding of Jamestown in 1607; what journeys they undertook were mostly by boat or ship. But as English settlements spread north and west, efficient overland travel became important. In 1632, the Virginia House of Burgesses passed the first road legislation, making the parishes in the colony responsible for road construction and maintenance, but that activity shifted to county court houses in 1657. Ten years later the General Assembly required every county appoint “surveyors of the highways who shall lay out the most convenient wayes to Church, to the Court, to James Town, and from County to County.”

To the north of Jamestown, settlers followed an Indian trail that ran up the Northern Neck between the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers. Settlers cleared and widened the trail as far north as Aquia in Stafford County by 1667. Since the Assembly chartered a ferry service across the Occoquan River in 1684, the road must have reached that far north by then. David Strahan began operating a regular ferry at what later became the town of Colchester in 1691, but Colonel George Mason, acquired the charter in 1744.

The road north through Stafford, Prince William, and Fairfax counties became known as the Potomac Path and it generally paralleled the river. The Path crossed each of the many creeks and tributaries at the first passable ford. Once across the Occoquan, the antecedent Indian path veered away from the Potomac and continued north toward the center of what became Fairfax County.

George Washington’s Era:

Boosted by the burgeoning tobacco trade with England, prospective planters sought land north of the Occoquan. In 1674, George Washington’s great-grandfather, John, and fellow speculator Nicholas Spencer acquired the land upon which Mount Vernon would be built later. George Mason II began buying land in the 1680s and 90s. (There were six George Masons in the main branch of the family, with Colonel George IV being the master of Gunston Hall.) In response to the growing agricultural enterprise, the Assembly ordered the establishment of tobacco warehouses on the Potomac and “rolling” roads to allow planters to get their crops to those warehouses and ultimately to ships on the river. Growers packed tobacco leaf in large, wooden barrels—hogsheads—that could be rolled on their sides or pulled by horses by hitching them to stubby axels on each end of the barrel.

By the 1730s, there were warehouses at Occoquan, Pohick Creek, and Great Hunting Creek. The community that grew up around the Great Hunting Creek warehouse was named Belhaven and, in 1749, became Alexandria.

The tobacco trade, plus social and commercial communication between the growing port of Alexandria and the planters to the south, used two overland routes. Both began at the first ford of Great Hunting Creek, called Cameron then and now (it’s the intersection of Telegraph Road and the Beltway). The Potomac Path, or the “river” road because of its proximity to the Potomac, followed what is now North Kings Highway up the hill to today’s Penn-Daw, then south to Gum Springs, the first available ford of Little Hunting Creek, then south and ultimately on Tillet’s Rolling Road to the ferry at Colchester. The “back” road followed a route that is today’s Telegraph Road to its current intersection with Route One, where it rejoined the river road to Colchester.

This circa 1767 map sketched by George Washington shows the Potomac Path between Colchester and Gum Springs. The route remains today as Old Colchester Road north to Pohick Church, then Poe Road (on Fort Belvoir grounds) toward Washington’s gristmill. North from the gristmill to Gum Springs is a combination of Old Mill Road, the remnants of the Pincushion Road right-of-way, and Buckman Road. Base map courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Both routes are shown on the oldest existing map of Fairfax County, circa 1745-48, drawn by Daniel Jennings. General Washington’s diaries and maps, however, shed more light on the Potomac Path during the second half of the 1700s. His 1767 sketch of the roads near Mount Vernon shows the Gum Springs-Colchester portion of the Path, as well the back road, which he labeled the Alexandria-Colchester Road. The map shows both routes intersecting Pohick Rolling Road (now just Pohick Road) near the current site of Pohick Church.

A recent Fairfax County tax map reveals the original right-of-way for Pincushion Road, part of the Potomac Path that dates from the early 1700s. The route of the road remains defined by the property lines of the adjacent land parcels. In the upper right-hand corner, the current Buckman Road is a vestige of the Path northeast to Gum Springs.

The route of the Potomac Path during Washington’s time at Mount Vernon still exists (see Figure 2). South from Gum Springs, it is now Buckman Road just to the north of Route One, and it continued south through what is now the Mount Zephyr neighborhood to its intersection with Washington’s private road to his gristmill on Dogue Creek, now called Old Mill Road. Washington referred to the lower section of the route as “Pincushion Road.” The actual road disappeared in the 1930s, but its route through the area remains in the form of shared property lines through the neighborhood. The old right-of-way can be seen at the Lukens-Old Mill intersection. The word pincushion is derived from an odd-shaped rock on the road called the “Devil’s Pincushion;” Washington referred to the area near the road “the Pincushion” and hunted fox there frequently.

The Path continued down Old Mill past Mount Vernon Country Club’s practice range, then through the woods to the gristmill. From the mill, the Path went up the hill and through what is now Fort Belvoir to its intersection with the back road (Telegraph). The 1767 route through Fort Belvoir remains largely intact—the Army calls it Poe Road—but its intersection with Old Colchester Road is gone (see Figure 3). Old Colchester Road is the Potomac Path paved over, and after crossing Mason Neck, it deadends at the Occoquan River. This is the former site of the Colchester ferry, and the few houses nearby are all that remains of the colonial town of Colchester.

Most of the Potomac Path in Washington’s day was primitive in design and maintenance, and rain made several key sections impassable. The General’s 1772 complaint about “Accatink” was common among fellow travelers. (Correctly spelled “Accotink,” it later became a village on the creek of the same name at the current intersection of Route One and Backlick Road.) Washington and Rochambeau encountered similar problems when they rode south to engage the British Army in Yorktown. A portion of their route over the Potomac Path south of the Occoquan still exists today. In Woodbridge, turn left off of Route One onto Longview Drive, then pick up Colchester Road to the south. Colchester, which turns into Blackburn Road, is the asphalt and concrete version of the Path.

The ferry at Clifton’s Neck (site of the Collingwood mansion on the Parkway) opened in 1745, permitting travel north to Baltimore and Annapolis. The Potomac Path thus became part of the King’s Highway, the main north-south post route in the colonies.

Turnpikes:

The distinction between the two routes between the Occoquan River and Great Hunting Creek arose first because the riverfront planters wanted a road closer to the Potomac. But competition for the crossing of the Occoquan was also important. In 1793, John Hooe began operating a ferry near the Occoquan mills (now the town of Occoquan) two miles upstream from the Colchester ferry. Two years later, Nathaniel Eillcott replaced the ferry with a bridge, a convenience that immediately drew travelers away from Colchester. A cutoff between the bridge and the intersection of the back and river roads at Pohick Church soon opened. The corresponding modern roads are the first mile of Ox Road north of Occoquan, then Lorton Road east toward what is now the intersection of Route One and Pohick Road.

Thomas Mason, son of George IV, built a wooden truss bridge at the Colchester ferry crossing, giving the name “Woodbridge” to Thomas’s nearby plantation. Its destruction by a flood in 1807 marked a decline in the Potomac Path’s role as the main commercial route south of Alexandria. By 1812, the mail stage shifted to the back road, a more direct and easier north-south route.

The first half of the 1800s saw a marked upsurge in road building, especially turnpikes. Financed by tolls, the roads featured a horizontally rotating wooden shaft or timber—a pike that turned, which kept non-paying travelers off the road. Entrepreneurs built the Hunting Creek Turnpike about 1810. It crossed Great Hunting Creek on a new bridge from south Henry Street in Alexandria to what is now the Fort Hunt Road and Route One intersection. The turnpike established a new route from Hunting Creek to Penn-Daw, then continued south on what is now King’s Highway South to its intersection with the back road to Occoquan (see Figure 4).

In 1856, the Alexandria, Mount Vernon, and Accotink Turnpike opened. It ran from the Hunting Creek bridge south along a route that is now Fort Hunt Road. It turned southwest on the current Sherwood Hall Lane to Gum Springs, then south along a new, direct route to Accotink that would later become the current Route One. The turnpike route between Gum Springs and Accotink straightened out the “S” curve of Buckman and Pincushin roads, much like the vertical line on a dollar sign.

By the Civil War, all of the antecedents to Route One were in place. Going north from Colchester, the roads that became the highway were Colchester Road, Poe Road, part of the Accotink Turnpike to Gum Springs, the “Mount Vernon” road to Penn-Daw, then the north end of the Hunting Creek Turnpike to the bridge at Hunting Creek.

Automobiles:

Virginia first appropriated funds for road construction in 1908. The Potomac Path gained the name Richmond Highway and by 1914, the section between Alexandria and Gum Springs had a thin coating of asphalt. The rest was dirt.

The U.S. Army acquired 1,500 acres in 1910 for a new installation--Camp Humphries. The land had been part of Lord Fairfax’s old Belvoir estate. (The Army renamed it Fort Belvoir in 1935.) After America’s entry into World War I in 1917, the traffic between Alexandria and Camp Humphries almost destroyed the crude road. (See Figure 5.) Using funds from the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1918, the Army laid an eighteen-foot-wide concrete road along the Accotink Turnpike route north to Gum Springs, along what is now Fordson Road, up Snake Hill (Figure 6) to the current Popkin’s Lane intersection, then onto Penn-Daw and the Hunting Creek Bridge.

The Army simply paved the old route, changing little of the line and grade of the old turnpike. A couple portions of the original concrete remain—the driveway into Woodlawn Stables and a road that runs parallel to Route One on Fort Belvior grounds between Woodlawn Baptist Church and the main gate. You can see it just to the right of today’s road and it merges into the current right-of-way next to the Woodlawn Road traffic light.

The Potomac Path and many succeeding roads followed the nap of the earth and the route of least resistance because roads crews lacked the machinery to do much else. The newer versions of the Path bypassed some of the colonial routes in favor of easier curves and grades. That was the case when Virginia began construction of the modern Route One in the 1920s and 30s, thus leaving some portions of new road parallel to the older roads. That approach allowed parts of the older routes to remain visible today.

Virginia designated the improved Potomac Path route “State Road 31,” then U.S. Route One. Remnants of older roads are scattered along the current right-of-way: Old Richmond Highway (5900 block) by Heritage Chrysler/Chevrolet, a track through the woods by Ourisman Ford, and Fordson Road, both at Lockheed Boulevard and in Gum Springs. Old Colchester Road parallels the current route to the Occoquan River and stands as a mute reminder of 300 years of travel on the Potomac Path.

History is more interesting when you can see tangible links to the past, certainly more stimulating than words. We often focus on buildings when thinking about history--Mount Vernon, Woodlawn, and Pohick Church for example—but the road between these places is almost as meaningful as the buildings. You just need to know where to look.